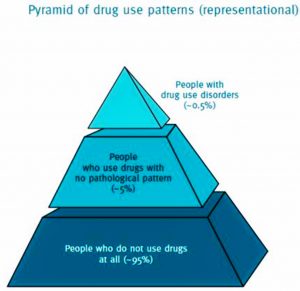

In this pyramid representation of drug use patterns, those in the middle, use drugs but not pathologically. Only a small number of people in the topmost layer suffer from drug use disorders. That group usually needs medical treatment and according to a 2017 report by the UNODC, some 10% of people who use drugs are suffering from drug use disorders and need treatment. Not everyone who uses drugs requires medical treatment and can be a waste if they are forced to undergo medical treatment. Instead, services that should be provided include counselling, health education (promotion) and psychosocial supports.

What Policy Says…

Building safe and healthy communities by minimizing drug related health, social and economic harms is the aim of 2018 National Drug Control Policy (NDCP). The following are the main principles; i) To shift towards an evidence – based, and health focused approach in developing drug legislation. ii) To create practical strategies, to address both illegal and legal drugs. iii) Develop a long-term plan. iv) Promote a whole-of-society approach, starting from the individual level to institutions. The NDCP also wants to move away from compulsory treatment systems to voluntary treatment systems using a variety of treatment options. Services must also be accessible and focus on reintegration into community. Policy advocates call for more community-based programming and substantive involvement of peers in the treatment and rehabilitation processes.

What is happening?

Globally and regionally speaking “drug treatment or rehabilitation” centers do not offer effective therapies based on scientific evidence. Instead, people in such centers are often subjected to long hours of forced labor, denial of vital medications like opiate substitutes or antiretrovirals for AIDS, lack of adequate food and water, and, sometimes, military like drills (harsh physical drills), etc. These abuses are akin to torture, and are commonplace in some drug treatment centers, both public and private. People endure such treatments because they feel they have no other options. Rather than turning to forced labor, corporal punishment, or harsh physical drills, officials would be better off addressing fundamental issues such as poverty, lack of education, or discrimination, in order to curb drug use in the community. Prolonged institutionalization for the treatment of drug dependence, particularly when accompanied by such methods mentioned above, is more likely to induce negative impacts rather than addressing drug addictions.

Providing quality rehabilitation services for drug users has become more important more than ever in the country. 2018 saw massive changes in the rehab philosophy and practice in the country. Previously, there were 2 types of rehab centers – i) a youth development center run by the Central Committee for Drug Abuse Control (CCDAC) which is under the Ministry of Home Affairs, and ii) rehab centers run by the Department of Social Welfare under the Ministry of Social Welfare, Relief and Resettlement. With a massive increase in drug use in the country; rehabilitation became more important than ever. And the government decided to set up a new department named the Department of Rehabilitation (DoR) under the Ministry of Social Welfare, Relief and Resettlement. Right after its establishment, with the guidance from top officials, all other rehab centers operating under the CCDAC were handed over to DoR starting in late 2018. This Department should regulate and administer Rehab Services operated by service providers in different communities. The department should ensure nationwide compliance standards that follow the international norms and respect human rights. However, there are no standardized guidelines and principles for both public and private rehabilitation programs in the country. There is also little respect for human rights and the desires of drug users to select treatments that suit their needs. Many of these treatments and services are also involuntary – either in part or whole.

Unpacking the realities on the ground

Sometimes, confusion occurs even among the responsible officials, as the Ministry of Health and Sports is responsible for the treatment of drug dependency whereas rehabilitation and social integration are under the Department of Rehab under the Social Welfare Ministry. This bifurcation will lead to delays and uncoordinated responses along the continuum of treatment, rehabilitation and social reintegration. We are seeing this occur now. It is not only challenging that these two ministries (under civilian government) are not well coordinated at practical level, we must also consider the role of the police who operate under the Ministry of Home Affairs, as they arrest drug users, often at the behest of concerned parents, caregivers and local (civilian) authorities. Politically saying, this is an area where civil-military relationships come into play, and it should not be omitted. These complications highlight the need for institutional mechanisms to be in place among concerned ministries and departments with concrete inter-departmental coordination both at horizontal and vertical management lines.

There is also the need to expand health services to local communities which requires great expense of human and financial resources. We must remember, not all drug users need medical treatment, rather treatment measures can be supported from family members, and talking with a lay counsellor within the community. Both international and national guidelines and policies mention the crucial role family supports and psychosocial community supports can have in treating non-medical drug addiction cases. Helping family members to change their perceptions to better understand that their loved ones who are addicted to drugs are suffering from health issues is the most important measure in the rehab spectrum. More efforts and investments are required in this area. Counselling (initial or follow-up) can be done by psychologists or lay counsellors who have the basic skills, but we are becoming overly reliant on psychiatrists. The culture of seeing health issues solely from a clinical perspective limits the ability of local counsellors to holistically involve in community-based rehab.

Community and faith-based organizations also run rehabilitation centers and they too play a crucial role. It is unrealistic to believe that the government is going to cover everything. However, care must be taken with how these centers operate. “Pat Jasan”, for example, is a community-based organization striving to eradicate all drugs from Kachin State. Its method is criticized to be harsh since they detain drug users even without due authority. This includes locking them in a detox room for two weeks where they receive no medical attention or care while suffering withdrawal symptoms. This is clearly a violation of human rights with significant negative impacts. We need to boost the reach of quality rehabilitation services which adhere to and protect human rights in every corner of the country.

Community-based rehabilitation services require a coordination structure with the meaningful involvement of civil society organizations and the drug users’ community/ networks.

Re-integration is one of the hardest components of the rehab spectrum. Vocational training, creating income generating opportunities and improving employability are all necessary, and hard to implement. For example, providing vocational training in agriculture is not applicable to those living in urban areas, likewise training in mobile phone repairs will not be useful without the involvement of the private sector. Market accessibility, relevant training, investment, private sector involvement and adapting to local needs must be included in any vocational training program.

This is just the tip of an iceberg. We are still in the infancy stage of addressing these issues.

Life, not the number

This is a reminder that the goal is to improve the situation for all concerned actors, while also protecting people who use drugs. We must prevent drug rehabilitation programs or treatments that are inhumane. We need action, collaboration, concrete procedures, break with old cultural stereotypes, involvement of the private sector, civil society, and the drug users’ community. We also need fiscal investments from the state as well as individual donors, and we need the political will to see favorable outcomes in the near future.

Above all, what we need is good intentions with righteous and humane approaches to deal with this issue. The latter part for me is the most important as we are dealing with the lives of individuals, whom we are aiming to change positively and re-integrate into our society.

It is not the number of people who graduate from the rehab programs, it is the number of lives successfully reintegrated into society that we must care about.

References:

- Republic of Union of Myanmar, National Drug Control Policy (2018)

- National Strategic Framework on Health and Drugs: A Comprehensive Approach to Address Health, Social and Legal Consequences of Drug Use in Myanmar, 2020

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime: Community Based Treatment and Care for Drug Use and Dependence, Information Brief for Southeast Asia https://www.unodc.org/documents/southeastasiaandpacific/cbtx/cbtx_brief_EN.pdf

- Unbalanced: Review of the Amended Narcotic Drugs & Psychotropic Substances Law against the National Drug Control Policy of Myanmar

- Wolfe, D., & Saucier, R. In rehabilitation’s name? Ending institutionalized cruelty and degrading treatment of people who use drugs. International Journal of Drug Policy (2010), doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2010.01.008

- TREATED WITH CRUELTY: ABUSES IN THE NAME OF DRUG REHABILITATION, https://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/uploads/7aa8663b-7bba-4000-801c-2f5fe415e45f/treatedwithcruelty.pdf

- https://www.mmtimes.com/news/drug-rehab-centres-placed-under-different-ministries.html