On 25 or 26 May this year, Mon people will be commemoration the Fallen Day of Hongsawatoi in Monland, Thailand and in many part of the world. This reflection piece is an account of the events of the Mon people based on the literature written in Mon, Burmese and English.

Old Monland Hongsawatoi (Hantharwaddy), or Pegu as it is known today, was a sea of Red and White on February 20 as large crowds of people dressed in traditional Mon garb gathered to celebrate Mon National Day. Even members of the Thai-Mon community visited the city to participate in the festivities. The event was a proud moment, applauded by all who were present.

Mon people have a rich history that today has resulted in a complex social, cultural, and political climate for Mon people spread between Thailand and old Monland. During this critical juncture in time, examining the glory of the past and re-assessing Mon identity is necessary to reclaiming Mon self-rule. The article will examine historical events of the past five hundred years that demonstrate the relationship between the Mon from old Monland and the Mon in Thailand. This essay will examine the social, cultural, historical, and political elements that connect the Mon people in old Monland and Thailand to offer insight into the debate over the current democratic transition in both nations. While focusing on the greater interest of the Mon people in the two lands for further national consolidation in terms of encouraging Mon people to take on major roles at institutions in both places.

Social and immigration transformations

The Mon village, Sangkhlaburi, in Kanchaniaburi province in Thailand has been living in social, cultural, and political transition for almost one hundred years. When Mon people arrive in Thailand, either for work and/or to visit family, they can usually speak Thai within a few months. Marriages between Mon and Thai children have been established in almost all Mon villages along Thai-Burma border. Mon migrant workers have been following Thai social and cultural norms. A Mon child can learn Thai language in school and assimilate into Thai society. A majority of Mon people are Buddhist followers with significant ties to a traditional Theravada institution. According to John F. Cady,

“The Mons were widely dispersed and poorly integrated. They were seldom dominant politically, but were important both economically and culturally. Their substantial economic skills as hydraulic agriculturalists, craftsmen, shipbuilders, seamen, and traders were matched by their civilizing role as transmitters of Indian culture. Indian governmental practices and kingship symbols, Vishnu worship, Buddhism, and Sanskrit and writing systems were all transmitted by the Mons to Burman neighbors, to Khmer cousins located to the east of the Menam valley, and finally to the later-entering Thai peoples.”

Mon migrant workers, exiled people, and scholars have been residing in Thailand for over fifty years. Many Mon people have stayed in the Mon monastery, where they could learn Thai and be ordained into monkhood under the patronage of Rev. Uttama, the founder of Wat Viwekaram (also known as Wat Lungphoh Uttama) in Sangkhlaburi, in Kanchanaburi province. Mon monks from old Monland graduated from that Thai Monk’s Literacy Examination Board with a ‘Teaching Qualification’ in Buddhism in Thailand.

The story of Mon merchant Magadu (also known as King Wareeroo) during Sukhothai era of the 12th century is one in the living memory in both Mon and Thai political literature. The Sukhothai dynasty flourished around 12th century with its trading between the people of Sukhothai and Martaban (known as Mutamah in Mon text). A Mon merchant Magadu traded with the people of Sukhothai using elephants. He was eventually employed to be a Chief Guard of the Royal Elephant Troops in the palace because he acquired great knowledge and skills on guarding elephant troops. He was given a title of ‘Jao Dhon Damrong’, Chief Guard of the King Sukhothai’s Royal elephant troops.

Magadu fell in love with the King’s daughter, Mae Nang Sai Dao, during his tenure. The couple fled back to Martaban while the King was at war with Kumbuja (or Kumbucha troops). Magadu consolidated power in Martaban. Magadu, as son-in-law of King Sukhothai, reestablished a royal connection with his father-in-law after he took over Martban. Since he was officially approved by the King of Sukhothai, he was given a new title as ‘Wareeroo’, as a great commander who attacked the Burmese king in Martaban and occupied the city with his greatness. This account of story is widely found in Mon, Burmese and Thai political literature.

Cultural and language transformations

Mon culture and language revitalization efforts in both Thailand and Myanmar picked up in the late 1960s due to Mon monks and Mon literature scholars. Efforts by monks and community leaders to re-open Summer Mon Language Courses have been widely supported by Thai and Mon scholars.

Naming a child in Mon language reemerged or in the late 1980s in old Monland while the Mon in Thailand retained the Mon textual scripts in Mon phonetic. By the late 1990s, Mon migrant workers and children were learning Mon language, music, and dance during public school holidays in major cities such as Bangkok, Samusakhon, and Kanchanabri . Thai-Mon community leaders and local monks formed a working committee for teaching Mon Language in Thailand and opened Mon language courses in Bang Kradi village (Bangkradee) in the Bangkok District. This year marks its sixth graduation anniversary to the cource.

From the establishment of the Mon dynasty in early 5th Century to it’s fall in the late 17th century, gift exchanges and and inter-royal marriages occurred between the Mon and Thai, according to both Mon and Thai history books.

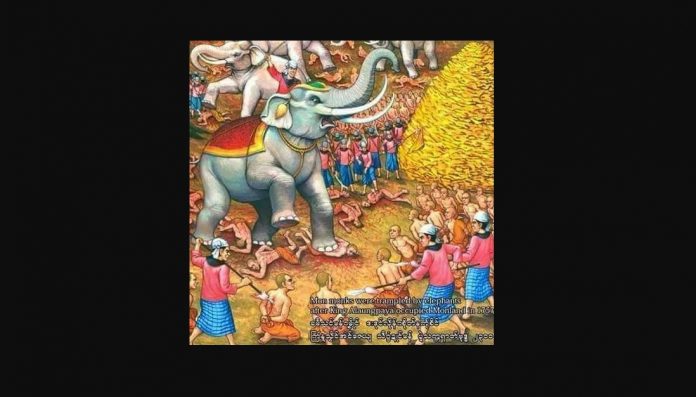

The Mon and Thai envoys crossed borders with elephants, and men travelled often during the cordial period between the Mon and the Thai. A royal visit was made on ceremonial occasions, but both nations faced tragedy during war with the Burman (Bahmar people) in a long war during 15th century, and on again on following occasions until the Bahmar people were defeated in 1760s in Ayudaya.

The cultural exchange of music, marriage, and traditional beliefs has continued over the past five hundred years between the Mon and Thai. In July 2018, The Nation Newspaper noted, “a traditional form of dance-drama known as ‘Lakhon Phanthang’ that first made its appearance as commercial theatre under royal patronage in the nineteenth century comes back to life … through an adaptation of the Thai literary classic “Rachathirat”, in Bangkok was a highlight of the significance of the drama and art of the Mon people in both nations.”

Paphatsaun Thianpanya in a lecture to Assumption Commercial College in Bangkok asserted that ‘the Mon literature which has influenced Thai literature are Rajadhiraja and Dhamasastra. The Thai translation of Rajadhiraja lead by Chao Phraya Phra Khang [Hon] in 1785/2328 is considered well written, and part of the story is the text for Thai secondary students in Thai language subject. The Mon Dharmasastra (or Dhamasak), had been mentioned as the source of Thai law in ‘Kotmay Tra Sam Duang’ [The Three Seals Code], a code of law compiled in 1804/2347 during the reign of King Rama I the Great”.

Thus, history shows that the Mon have had independent states of their own tracing over 2,500 years. The most known in latter days history was Rehmonnyadeca or Hongsawatoi (Homsavati or Hanthawatee) or currently known as Pegu Region (Divisin) covering the whole of Lower Burma until it was wrested away by the Burmese troops in 1757. During the periods when the Mon were masters of lower Burma, the people were happy and prosperous. Those glorious periods were described by distinguished historians as golden ages under wise Mon rulers. Relations with foreign countries and foreign nationals were peaceful, cordial, and harmonious. That was when the Mons blended their native culture with Theravada Buddhism, which elevated them as teachers of their homeland until modern era.

More than half of the Mon population migrated into Thailand where they were given refuge and treated as equals. The Mon, back when they were masters of Thailand, received the Thais with open arms when they migrated south from Yunan. This time, it was The Mons’ turn to receive the Thais’ hospitality. Hundreds of thousands of Mons returned back to Burma – their old homeland – when it came under British rule.

The Nation Newspaper did a story about the Thai–Mon in its English Newspaper in March 2018:

‘members of an ethnic Mon family in Bang Kradi perform a traditional dance, but their intent is not to catch the attention of neighbours and tourists visiting Bang Khunthian district in Bangkok. The show, which is called Ram Phi Mon, or Mon ghost dance, is specifically organised to please the ancestors of long-deceased relatives’.

In fact, the living treasure of both Mon in Thailand and in old Monlandm has been revitalized in both nations in recent times.

Historical and Buddhist institution exchanges

In the last decade, the Mon Cultural Centre based in Sangkhlaburi organized and sponsored Mon traditional, classical and contemporary musical instrument instructors and teachers for the training in the new Mon Musical Instrument Course. Nai Kasuah Mon, director of Human Rights Foundation of Monland, sponsored the Mon Music Teacher from old Monland to go to Thailand for both training and ceremonial events as an exchange of art and learning of the Mon musical instruments.

The first historical turning point has been well acknowledged in both the Mon Royal Chronicle and Thai historical society. Prince Naresuan declared on May 3, 1584 that Siam rejected the state of the Burmese king in the town of ‘Gine’ or ‘Krang’ at the bank of Gine – Sittaung River in old Monland. Prince Naresuan was informed by the two Mon commander or ‘the chiefs’, that he would be assassinated by the Burmese king if his kindom came under the control area of the Burmese capital. Thai historian, Professor Syamananda (1973), accounted the event in the book titled ‘History of Thailand’:

Naresuan left Phitsanulok with an army for the Burmese frontier in February 1584 and in accordance with his dilatory tactics, he arrived at the Mon town of Krang ‘Gine in Mon tetxt’ on the Thai border in May of the same year. Should Nandabureng (aka – Nanda Bayin or King Nanda in Burmese text), suffer defeat at the hand of the rebellious Prince of Ava, Naresuan would attack Hanthawadi at once, and in the event of the contrary, he would move back the Thai inhabitants, who had been transplanted to Burma, so as to augment the population of his land. The Burmese Crown Prince (The son of Nandabureng), had in the meantime, entrusted two Mon chiefs, Phya Kiart and Phya Ram (aka – Banyeh Kindell and Banyeh Rahm – in Mon Text), with a descreet mission to murder Naresuan, but they balked at the act and disclosed the whole plan to him, due to the fact that the Mon entertained strong hatred against the Burmese. Prince Naresuan therefore called a meeting of all his generals and the Mon officials who had very recently transferred their allegiance to him and, with his father’s full consent, he proclaimed the independence of Siam at the town of Krang on May 3, 1584, thus terminating the Burmese vassalage of fifteen years. Most of the Mons at Krang sided with the Prince and helped him in his advance to Hanthawadi.

After close to two hundred years of relationships and inter-marriage and military operation against the Burmese kings, Mon in both nations consolidated their influence to unify the two dynasties; Ayudaya and Hongsawadi have exchanged social, cultural and political institutions since A.D, 1584 in close connection of alliance.

Historically, according to a Mon royal chronicle, a Mon monk Pali and Thai scholar by the title of ‘Phra Tarai Tisarana Dhaja’, toured old Monland as laymen after he disrobed from monkhood in Siam. He arrived in a Mon village, Sung Kha Pine village near the bank of Sanlwin river in A.D, 1874 (Lunar Era 1236). He established a new Buddhist Learning Centre (Monastery) in 1875 in Ka Doe village, and introduced a new institution ‘Dhamma Yutti Nikaya’ in old Monland with his fellow learners. Since his child name was ‘Mehm Yin’, the Institution was also known as ‘Maya Yin Gine’ in Mon and Burmese terms. After twenty years, he returned to Siam in order to reunite with old Monks, teachers and fellow learners. The monk was called ‘Buddha Wongsa’ when he was first ordained in the monastery of ‘Pawara Niwesa Vihara’ in Bangkok, but his native birthplace is Krung Garu village in Samutakhon province, about thirty – eight kilometer to the southern of Bangkok. The legacy of this socio-cultural Buddhist institutional transformation took off in many parts of the Mon community and created changes that still exhist today. The monk who founded ‘Dhamma Yutti Nikaya’ passed away in 1916 at the age of 76 in his monastery in Bangkok. In modern era, Mahayin Gine (Mayayin Nikaya), is the third largest Mon Buddhist monk’s council with highly regarded chief monks who teach Pali and Mon text in many part of the current Mon region / state.

Political aspirations and Royal exchange in socio-political transformations

Mon political activists, leaders, and students took refuge in Thailand in the early 1950s, after Burma gained independence from the British in 1948. Almost everyone, key members of the New Mon State Party or other Mon political organizations, such as the Mon Unity League, the Mon National Democratic Front, and the Mon People’s League, visited and temporarily stayed in Thailand for the movement of self-rule in Monland. Mon monks and other non-political groups, such as Mon language, music and business people, also resided in Thailand, especially in border areas.

Mon descendants based in Thailand also established Thai-Raman Association in the 1940s and Mon Youth Community – Bangkok in the 1970s in collaboration with Mon people from old Monland, prominent Mon monks, political figures, and scholars. The program has offered exchange visits, seminars, and political conferences over the past fifty years in non-violence pursuit of Mon self-rule (or self-determination) in old Monland.

The late Nai Shwe Kyin (1913 – 2013), the founder of the New Mon State Party (NMSP), resided in Bangkok from the 1960s to the 2010s, occasionally working on external / foreign affairs in various roles, with the kind support of Thai-Mon people and other democratic friends of Thailand and Burma.

After the 1990s, Mon university students, youth, and young monks also resided in Bangkok, especially Wat Prok, (Mon Temple in Yanawa District), in the heart of Bangkok for shelter. They started a democratic movement in collaboration with Thai – Mon people and Thai nationals who were members of Thai Action Committee for Democracy in Burma (TACDB), Thai Human Rights Forums, and senators of Thai Parliament who were key supporters of democratic changes in Burma. In fact, Overseas Mon Student Organization and Overseas Mon Young Monks’ Union were founded in 1990s in Bangkok.

The best case to be noted is that Mon Information Services (MIS) was formed in the late 1990s in a joint effort between Thai-Mon and Mon from old Monalnd. The publication of Mon news in Mon, English, and Thai language has increased its publicity under the sponsorship of Mon Unity League and other non-disclosed funds. In the late 1990s, Mon National Day celebrations were publicly held in Bangkok in a joint-initiative of Mons between both nations. Thai Student Unions and a few Thai human rights activists also assisted in holding Mon National Day events at various venues, including on the University campus. Mon people between two nations have exchanged information and knowledge on promoting human rights and democratic movement during 1988 – 2008 until Burma called a new Election in 2010.

Historically, after Burmese (Burman) attacked and sacked Hongsawatoi (or -Hanthawadi) from 1756-1757, the Mon fled to Thailand (Ayudhaya) and established a new self-ruled area in Ratpuri regions under the patronage of the Siam (Thai) dynasty since, the Mon’s remaining royal troops were granted resettlement on the land. Banya Mahayodhao (aka Banya Jeon) led the Mon self-ruled area in Prathum Thani and Thonpuri regions with his troops and associated families starting in 1775. According to the Mon Royal Chronicle, this settlement was the foundation of ‘Banyi Ramanya Wunsa Army’ under Commander in Chief Samhain Jekkari Mon under the patronage the His Excellence, Thaksin, the King of Thonpuri.

Nai Dhira Sumhlaike, a Thai-Mon historian and Thai-Mon radio presenter noted that since the death of King Thaksin (Prajao Thaksin in Thai text) in 1782 A.D., Samhain Jekkari Mon ruled Siam under a new title of King Rama Dhipati. Since the title “Rama’ has been widely used in royal terms, his successor has been named in order of the number of the crown, as King Rama the second and the third, continueing until the most recent King of Thailand in Siam history.

(Inserted note: this author has met Nai Dhira on many occasions between 1994 – 1996 during temporary stay in Thailand).

After being under Burmese rule for 67 years, Tenasserim Division, which formed part of old Rehmonnya, fell into the hands of the British together with Arakan Division in 1826 after the First Anglo-Burmese War. The other part of old Rehmonnya covering the present Pegu and Irrawaddy Divisions fell to the British in 1854 after the second Anglo-Burmese War. Finally, when Upper Burma, known in the chronicles as Ava, was annexed by the British in 1885 after the Third Anglo-Burmese War, the whole of Burma came under the British as a colony until 1942, when the British withdrew from Burma during World War II.

A Mon historian and author, Layehtaw Suvannbhum, president of the Australia Mon Association, noted:

When the British government initiated steps for granting independence to Burma after the Second World War, Mons urged the Burmese political leaders, who were in power as Executive Councilors to the British Governor, to include satisfactory provisions and safeguards for them in the Constitution which was in the making. The Burmese chauvinists instead of ceding to the Mon aspirations waved it lightly by giving a far-fetched excuse saying that Mons and Burmese are indistinguishable in racial identity and characteristics, and separate minority rights should not be contemplated. But when the demand for the right of self-determination became popular and an upsurge of Mon mass support came to climax in 1948, the Burmese government took measures to detain some of the Mon leaders and assassinate many of them.

Nai Shwe Kyin, the late President of the New Mon State Party addressed Party Congress with a message delivered to the Mon people:

After nearly four decades of Burmese administration the country is politically in turmoil and economically in slump. That clearly indicates the historical failure of the Burmese leadership. To address the political, economic, social and military crises General Ne Win’s government had demarcated on Moulmein and Thaton districts in Mon State, Article 31 of the new constitution was published in April 1972 calling for a national referendum. In the same article Arakan and Chin Divisions were demarcated as Arakanese and Chin States respectively. The National Assembly had already approved the new constitution on January, 3, 1974. Thus the three states came into existence in January, 1974.”

This message was recorded in a book by Nai Pan Tha (2014) published in Burmese on the history of the Mon people’s movement for Political transition.

Conclusion

After close to five hundred years, the Mon people in two nations have been searching for their identity, cooperating both formally and informally in attempts to preserve cultural heritage and consolidate politically. A new Mon-Thai National Council shall be established for further engagement in terms of teaching language, promoting business opportunity, and consolidating land rights under the national and international native people’s rights to land, and helping with access to other local services provided by both the governments.

The old Mon kingdoms were destroyed by the Burmese Kings’ troops in the past seven hundred years but the identity of the Mon people in two nations has been proof that the Mon civilization is re-merging in the contemporary world.

MAY 2019, CANBERRA, AUSTRALIA