As raft-fishing businesses in the Irrawaddy[Ayeyarwady] region also known as the West Coast experience deforestation and scarcity of fish resources, many big boat operations are setting their sights on the Myanmar East Coast. The journey takes two days and there has been a notable increase in boat traffic, much of it in secret.

Raft-fishing operators from Irrawaddy [Ayeyarwady] have been gradually migrating into Mon fishing blocks and are contributed to human rights abuses, through forced labor and human trafficking. In addition, many of these are illegal business operations creating a loss of State revenue and threatening fish populations.

The number of raft fishing operators is enormous. Mon States’ Minister for Agriculture, Livestock, Transportation, and Communications, U Tun Htay described the situation this way,

“if we [connected] all the fishing rafts from Ayeyarwady region and Mon State [together] it would be possible to walk [on them] from Pyapon [Township], in Ayeyarwady to Mawlamyine [Mon State].”

The Hluttaw approved the need to take action.

Dr. Aung Naing Oo, Chaungzon Township Constituency (1) proposed in the 15th regular session of the Mon Hluttaw in February 2020, that sysematic measures are needed for the marine fisheries sector, in order to prevent human trafficking and human rights abuse of workers.

Between January 21 and 24, 2020, an inspection group that included the Department of Fisheries, the Fisheries Federation, the Department of General Administrative, police force members, and the media investigated the situation at sea.

Nyan Soe Win, a reporter from a news outlet, the Irrawaddy, who joined the group noted that in fishing blocks D6, D11, and D12, there were 1223 fishing rafts. Of these, 57 fishing boats could not produce their business licenses issued by the Department of Fisheries. More than 4000 fishermen working in these blocks were unable to show their fishermen cards.

He pointed out that,

“More than 1000 fishing rafts [have intruded into the Mon coast] from the Ayeyarwady as we found out during our visit for two days. If we were to stay longer, we would see many more. The fishermen said they came because there are ten thousand fishing rafts on the Ayeyarwady River, and it has been congested on the sea.”

According to the Department of Fisheries, there are 153 offshore licensed local fishing rafts and 1000 inshore fishing rafts in Mon State.

According to the local people, the numbers are much greater. Area residents suggest that about 2000 raft-fishing businesses operate offshore. They are thought to be from Abaw-Kyar-Than, Si Phyu Daung Kyar Than, Asin-Taemin-Sate, and an Andin fishing camp located in Ye Township.

Only a small number of raft-fishing operators have been investigated by the Department of Fisheries.

A member of the Ye Town Social Services unit (YSS), U Aung Naing Win, pointed out that raft-fishing owners have become more cautious with their operations. This is in part due to media reports of human rights abuses, particularly one case involving the trafficking of a university student from the Irrawaddy region last year. Also, the number of crimes in the raft-fishing business in Ye Township has been declining.

He added,

“there were about four to five criminal cases each month in our township, but it has been declining this year. It could due to the [media reporting] of the [human trafficking] case that happened in the Irrawaddy region. The fishing rafts helmsman have also become more cautious. Now they treat their workers better, and their employment relationship has improved. The owners of raft-fishing businesses seem to control their people [helmsman] better.”

However, on February 22, a criminal case took place involving a fishing raft,west of the Wa-Kyon, in Ye Town [river mouth], which was stationed 30 miles from the shore.

Ye Township police station charged the helmsman and one fisherman, under Section 302/144of the Myanmar Penal Code, for killing another fisherman with a sword. The altercation became violent after it was alleged the fisherman had not performed his duties well.

According to U Myo Win, a Ye resident and Amyotha Hluttaw representative,

“some fishing raft workers did not want to stay at sea. Things became violent, when the helmsman tried to stop [these] workers [for wanting to return to land]. Three to four criminal cases used to take place [involving] the fishing raft [operations] each month, and workers were killed from fights.”

Working conditions

U Myo Win, explained that inshore fisheries work involves eight hour days, with the potential of overtime pay. However, those stationed on a raft cannot earn overtime pay and have less hours for sleeping. The rafts, which range from 20-30 feet long, house one helmsman and two workers. This small group of workers can be together at sea, 24 hours a day for eight months. Under such conditions, of hard work, little rest and limited space, there is often high potential for fighting and mental breakdowns.

The growth of the industry has demanded more workers, and there is increasing competition amongst labor brokers to recruit new workers. Workers come from various backgrounds, some are inexperienced, unskilled, unhealthy, or are evading the law [wanted persons], or are deserters from the military or police. Others are homeless persons who are forced into labour at the hands of some criminal labour brokers.

Each fishing raft requires two to four workers, depending on the owner’s business operation. Experienced workers can earn a living from the job without having any difficulties, but inexperienced workers face many obstacles including physical abuse and violence..

One worker, Ko Min Oo describes the daily operation,

“A fishing net is thrown underwater every six hours. Once when the sea level rises and another time when the sea level goes down. This happens four times a day. We have to haul the net up four times and cast the net four times, following the sea current. The mouth of the net has to be opened wide and faces the direction of the water current. From there, fish and prawns enter the cone-shaped net, and they reach the narrow end of the net,where fishing bait is stored. All trapped aquatic animals gather with the bait. We haul in the fishing net and then harvest the fish.”

A group of 40 fishing rafts , where Ko Min Oo worked, has 40 helmsmen, who in turn are managed by one person who is in-charge of overall operations. This person sets the rules and gives penalties if there is no catch, or if someone has a serious illness, or is lazy at work, and other issues.

Ko Min Oo, described a harrowing incident in which a fisherman became a victim.

“One worker jumped into the water and went into the casting net, which later was hauled aboard the raft. The water was so strong that he could not [swim out of the net) and died, so I quit the job.”

Sometimes, the fishing equipment, like the wheels that haul the large nets aboard the raft, puts workers into great danger, such as breaking arms, legs or resulting in loss of life. In addition surviving in storms and high waves are not easy, particularly for those inexperienced with life at sea.

Workplace injuries or death is common in this very hazardous workplace. Misfortune also includes rafts being torn apart by storms, and workers being stranded at sea. There are no records of the number of raft fishing workers who have lost their lives due to such natural disasters. Likewise there are few, if any life vests or safety gear on board these rafts.

Raft fishing economics

Six hours after a fishing net is hauled aboard the raft, the prawns are selected and boiled, while large fish are sun-dried. The fishermen note the total weight of fish and prawns harvested. Apart from their annual wage, they will earn additional pay when they return to the shore during the fishing off-season in accordance with the weight and sale price of the harvest, explained Ko Thin Aung, a fishing raft owner.

Ko Thin Aung said,

“Depending on the sort of fish we get, [the prices range] from 200 Kyat per Viss (1.6 kilograms), and a better fish species could get 500 Kyats per Viss. Workers have to list [the harvest] based on the weight of captured fish. All workers have to make a list. When they get back to the shore, they can get paid for that. Last year, each [fisherman] earned about 700,000-800,000 Kyats from extra payment. This year, business is not too bad,”

Typically, eight months of salary for a helmsman ranges between 1,000,000 to 1,200,000 Kyats, and fishermen generally receive from 500,000 to 600,000 Kyats.

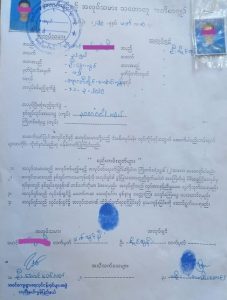

According to industry regulations, employment contracts between the business owner and workers are to include the workers’ names, father’s name, and address. However, the investigation team found that almost every contract they saw did not include any identification information related to the workers.

Other irregularities were found with these contracts. They were not official Myanmar government stamped contracts, which are to be A4 typed papers issued by the Ah-Sin village Fishery Business Operators Association and must be signed with a witness.

The contract included four main points:

- If the worker fails to start their working [day], he will have to pay back twice as much as the advanced payment.

- The worker will only receive half of his annual payment, if he leaves his job before the end of the year without the employer’s permission. The employer has to make a payment equivalent to the workload of workers.

- The employer must pay compensation, if any accident occurs in the workplace.

- The employer must handle situations where workers are injured or do not feel well.

Some workers reported to the investigation team, these terms were often not upheld.

The Ye Township Fishery Industry Department has been negotiating between industry owners for new ways and means to eliminate human trafficking, promote a fair payment system and issue proper registration cards for more than 4500 workers from inshore and offshore boats/fishing rafts, and fishermen.

In addition, Amyotha Hluttaw representative, U Myo Win added, that parliamentary representatives have held educational talks on the issues.

U Myo Win explained,

“If business owners only accept workers with registration cards, it will be easier for them to investigate and identify if a crime or complaint occurred at sea. Not only helmsmen but also the raft-fishing business owners could be affected if workers experience inhumane or forced labor. After visiting and discussing this with both sides, we have not heard of any related crimes in two to three months.”

U Myo Win further commented that stronger regulations are still needed for fishing raft workers. These rules and regulations must address in detail issues such as; working hours and salary, number of workers/raft, illness, work-related injuries, death, natural disaster protection.

In addition, U Myo Win argues that the industry must face operational inspections at sea involving the coast guard/ police forces. He estimates it could take at least two years to complete such regulatory, monitoring and enforcement protocols.

International implications

Some of Myanmar’s fishery products are imported to the European Union and other western countries creating revenue for both the state and business owners. In light of this international trade in fisheries, it is becoming more important for the industry and government to take careful steps to address human rights concerns, and the documented increase of forced labor and human trafficking cases.

Deputy Minister for Agricultural, Livestock, and Irrigation, U Hla Kyaw, told reporters on February 28, that fishery business owners and workers from raft-fishing industry operators based in England are required to register at the Department of Fisheries.

The Deputy minister U Hla Kyaw said,

“Workers there must be registered. For example, Mr. A.. is a fishery industry owner employing 33 fishermen. He must register those workers’ personal information including their identity and whereabouts at the Department of Fisheries. The owner must also get a license for his business. All of these [requirements] already exist. In some cases, however it did not seem to be effective particularly at times when there is a shortage of workers,”

The Deputy Minister pointed out that existing rules and regulations enacted by the Department of Fishery, Code of Conducts are agreed to by fishing raft workers and employers. This includes a 16-point employment contract that is carefully reviewed and is being revised given the current context.

This stands in direct contrast with the meagre 4 point contract the investigation team uncovered.

Season for change

To conserve fish stock, prawns, and other aquatic resources the fishing season starts to close down in April of each year. According to a statement released by the Department of Fisheries on March 23rd, during the breeding season, (June 1 to August 31), a complete closure of the fisheries applies for all domestic and international fishing vessels in the Myanmar fishing industry.

When the fishing season opens in early September 2020, the Mon State government will likely again have to address the migration of illegal fishing rafts into the east coast fishing blocks.