They are the final and most popular words being used in our country. The phrase ‘Union of Myanmar’ has dominated news, reports and features over the past hundred days.The 70 years of internal armed conflict, racial discrimination and distrust towards the public administration system have been healed by the public after a newly elected civilian government was formed in March this year. It is not a simple process but a process that our country ought to proceed, towards ‘peace, unity in diversity and restoring a faithful governance system’ within the spirit of a ‘federal model’ at large.

After reading two Burmese language versions regarding a framework for the ‘peace process’ released by the Government (a version during 2013-2015) and a lengthy discussion on the ethnic armed organizations alliance by the United Nationalities Federal Council (UNFC) in recent weeks, it is clearly prevalent that there is a clash of ‘political principles and ideologies’in the way we reach a peace agreement. However, both sides have to hold onto ‘good faith’ during this unforeseeable process.

1) To remain forever in the Union

2) To accept the Three National Causes: non-disintegration of the Union; non-disintegration of national sovereignty and perpetuation of national sovereignty

3) To cooperate in economic and development tasks

4) To cooperate in the elimination of narcotic drugs

5) To set up political parties and enter elections

6) To accept the 2008 Constitution and to make necessary amendments via Parliament by majority consent

7) To fully enter the legal fold for permanent peace and live, move, work in accordance with the Constitution

8) To coordinate existence of only a single armed force in accordance with the Constitution

The core eight principles are non-negotiable, referring back to the last NCA inking, but eight ethnic armed leaders signed the documents based on the ‘good will’ of the previous government.

The first obstacle to reach a peace agreement is widely publicised in the media regarding a core principle of the government (former military authority). Namely, its three national discourse areas; non-disintegration of the Union (under the formation of the constitution of the 2008 adopted model); surfacing irreconcilable differences as Lintner (2012) asserted that ‘there are now two fundamentally opposing views on how Myanmar’s ethnic question should be resolved. For the government, the solution to ethnic strife is for the rebels to lay down their arms in a gradual approach under terms stipulated by central authorities. For ethnic rebels, hopes are that the ceasefire process will through negotiations eventually lead to the establishment of a federal union and more regional autonomy’. However, Burma Partnership (2013) remains as hopeful that a ‘political dialogue will address issues that are difficult and messy, such as the power of the Burma Army, political power sharing between the central government and ethnic nationalities, resource management, and justice for human rights abuses committed by all sides. But if sustainable peace in Burma is the true goal of the Burma government, it must be willing to address these issues’.

Furthermore, the Economist (2015) asserts that ‘For now, however, the current setup suits rather too many. While ethnic armies enrich themselves in their regions through illegal trade and taxation bordering on extortion, some army officers even collude in it. In any political settlement, Myanmar’s government would have to give up some of its central powers, and the ethnic armies would have to cede much to the centre—presumably folding their militias into the national army or regional police forces’.

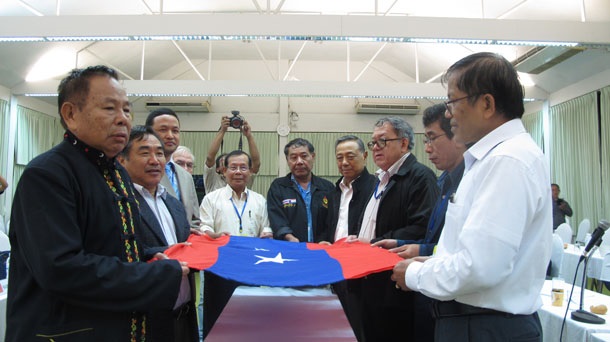

Ethnic Armed Groups Seek Common Ground; as reported from sources Saw Yan Naing / The Irrawaddy, recently reported that ‘Signatories and non-signatories of last year’s nationwide ceasefire agreement (NCA) will hold a meeting to prepare for an upcoming ethnic summit, where groups will cooperate toward building a federal union’.

The UNFC’s proposed its core 15 principles but the immediate key principles listed 1st- 4th below do not contain the word ‘federal’ as found to be creating room for improvement for further peace negotiations.

The Parties agree to the following principles:

1. Commitment to Peace, the Parties agree to work together to create a harmonious, prosperous, just, peaceful and modern democratic nation;

2. Acknowledgment of the Panglong Agreement, the Parties recognise that the Republic of the Union of Burma gained independence speedily in 1948 because of the 12 February 1947 Panglong Agreement which fulfilled Article 8 (b) of the Aung San-Atlee Agreement signed in London on 27 January 1947;

3. Union of Burma, the Parties agree that as signatories of the Panglong Agreement, the peoples of Kachin Hills, Chin Hills, the Federated Shan States, together with Ministerial Burma, are co-founders of the nation, and jointly share the responsibility to safeguard the Union of Burma (also called Myanmar) and;

4. Respect, democracy and autonomy, the Parties agree that, as the Union of Burma/Myanmar is based on mutual respect, equality, democratic principles, and full autonomy in internal administration as agreed in the Panglong Agreement, there should be no reason for anyone to secede from the nation.

The 15 principles of political negotiation proposed and agreed by UNFC’s leaders clearly affirm that the armed ethnic leaders only sign the paper if the government of Myanmar, currently the NLD’s administration, compromises the frameworks based on the ‘formation of a genuine federal Union’ in an agreeable model by representatives of the entire political organisation. The armed ethnic leaders avoided using the word ‘confrontation’ in regards to the established Myanmar’s Army (Tatmadaw) but the proposal for Peace Agreement clearly indicated that the 21 ethnic armed leaders will not disarm unless a new constitution is amended with a guarantee of sharing power on the three pillars of governance.

The Myanmar Peace Agreement is a process of ‘give and take’, as warned by the Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, the State Counsellor last month during a meeting with NCA signatories. Amid clashes of political principles and ideologies, it is the moment that a reform process should be included as these leaders are committed to lasting peace and national unity. It is the moment that a reform process should be included as these leaders are committed to lasting peace and national unity.

The last note is sourced by two Australian’s scholars from the Australian Federal System despite Australia and Myanmar displaying vastly different social and political cultures. However, their concept should be critiqued by armed ethnic leaders and Myanmar’s MPs as positive advice. Home and Sharman (1977) suggest that ‘federal structures stress a conflicting theme of constitutionalism which sees the need to check both the mode and scope of government action by entrenching certain in a constitution which yields the power of the legislature to amend’.

In fact, a new peace process should be a tabled to find room for improvement not just a piece of policy but also common rules to follow. Unless the first obstacle is fully addressed, the second and third obstacles will be hard-pressed to find agreeable solutions.

The next Peace Conference, or the 21st Pang Long Conference, will be an assembly of ‘room for improvement’ rather than peace solutions.