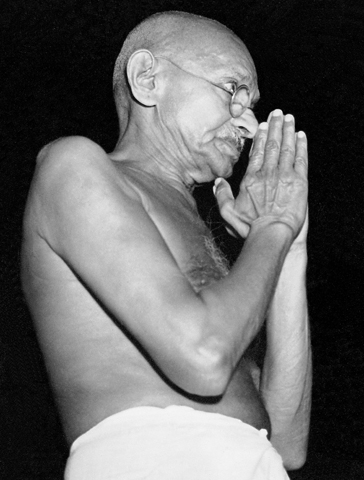

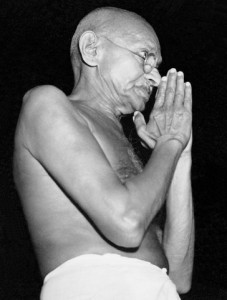

Nai Banya Hongsar – Burma and India have shared social and cultural ties since before the before the birth of Gautama Buddha, over 2,500 years ago. In the late 1800s, both countries were colonised by the British Empire, during nearly a century of forced assimilation and white domination in central Asia. However, in the 21st century, Burma and India exhibit two distinct and divergent realities. Burma has a population of less than 60 million and is considered underdeveloped, while India claims developing country status and has emerged to assume a prominent role as a regional power player in political and economic spheres. Today, it is useful for Burma to reflect on the two countries’ shifting commonalities from past  to present, and to consider the relevant lessons of promoting peace, restoring democracy, and building a democratic nation that embraces federalism within its particular context. Burma should seek, as India did, its own “Middle Way.” In contemporary political terminology, the “Middle Way,” or “mizzima padipada” in Pali, is known as “compromise” or a “win-win solution,” and represents a sense of balance, understanding, and shared responsibility. Burma’s current leaders are educated in the history of India and the legacy of Mahatma Gandhi’s more than thirty-year dedication to nonviolence, and Burma is in a prime position to experience a revival of Gandhi’s political application of the Middle Way.

to present, and to consider the relevant lessons of promoting peace, restoring democracy, and building a democratic nation that embraces federalism within its particular context. Burma should seek, as India did, its own “Middle Way.” In contemporary political terminology, the “Middle Way,” or “mizzima padipada” in Pali, is known as “compromise” or a “win-win solution,” and represents a sense of balance, understanding, and shared responsibility. Burma’s current leaders are educated in the history of India and the legacy of Mahatma Gandhi’s more than thirty-year dedication to nonviolence, and Burma is in a prime position to experience a revival of Gandhi’s political application of the Middle Way.

The Buddhist concept of Middle Way is well known in Burmese culture, largely due to religious centres where Buddhist monks lecture the public on how to apply meditation practices to the wider community. In contrast, Burma’s political leaders have, in the past, shown minimal interest in cultivating “Middle Way” in their political affairs. Racial prejudice as policy is common, evident in the fact that central Burmans have carefully safeguarded their power in the nation, while southern and northern hills people (mainly ethnic non-Burmans) have little capacity or resources to incite change. Burmese rulers who abuse the power of the state and exploit rule of law have gripped the nation for over sixty years. This entrenched mentality will only change if the ruling elites are forced to govern by public demand, or with the onset of alternative and competing military might.

Between the 11th and 13th centuries A.D., Burma’s great kings began frequently attacking, invading, and colonising much of Burma until the late 18th century, prior to British invasion. Burman royal troops clashed with Arakan, Mon, and Shan royal troops for most of the 17th century, until central Burma was finally under their control. In 1757, during the invasion of the last Mon capital of Pegu (“Hongsawatoi” in Mon), the formidable power of the great Burman Kings and the brutality of the Burman royal commanders resulted in the deaths of over three thousand Mon royal troops. According to Mon royal chronicles, Banyi Dala, the last Mon king, was assassinated at Rangoon River during the attack. Today, descendants of Mon leaders who fled to Thailand and current Mon political leaders in Burma have healed the historical wound with the sense of unity and mutual understanding found in Buddha’s Middle Way—the same that influenced the late Mahatama Gandhi.

According to the Mon Royal chronicles published by Mon historian Nai Palita, Arakan and Mon kings promoted cultural exchange between their nations and the northern Burmans from the 9th to 12th centuries, until the Burman ethnic group eventually developed its own unique language, culture, and identity. The latter’s gratitude toward Arakan and Mon Kings is well recorded in Mon literature. Many of the early Burmese foundations dating back to the 11th century are commonly regarded as being built by Mon royal circles, including the sites of Pagan ancient cities and surrounding pagodas in central Burma’s flat land.

Regrettably, the loss of the last Mon royal troops, entire Mon families, and the great civilization of lower Burma has not been addressed by Burma’s ruling elites. The new political movement in Burma, including students and the “8888” generation, was never more outspoken than in 2010 and 2011 when it called for the plight of ethnic people to be legally and morally acknowledged before the nation could effectively pursue peace in the future. But their message has not yet reached the heartland of ethnic people who have been oppressed by either Burmese or British rulers for over two hundred years. Despite the rhetoric of “unity, diversity, and national reconciliation” widely used by ruling elites in the past twenty years, in practice, the status quo of majority privilege and minority plight continues to dominate the politics of ethnic Burman and military-civilian officials. For this reason, Burmese scholars and spiritual leaders have been on the frontline of the battle for national unity for over sixty years. Burma’s writers and community leaders have advocated for healing the wounds of the past and seeking common ground as brothers and sisters.

After two hundred years of misunderstanding toward the diverse ethnic and native people in Burma, current leaders President Thein Sein and Daw Aung San Suu Kyi recognise native people’s painful loss of their kingdoms and royal families. They incorporate concepts like, “unity, cultural diversity, and respect for human rights”, which were rarely proposed or mentioned by Burmans in the past. Also, Burma’s leaders – including Suu Kyi, President Thein Sein, and Cabinet members – are now elected or appointed according to the nation’s constitution, and elections are an important stepping-stone toward reaching a political Middle Way. However, achieving the crucial sense of unity and harmony is beyond the scope of ideological contests. Formal policies and laws would be vastly improved if ruling elites, from all ethnic affiliations, incorporated the spirit of Gandhi’s Middle Way into Burma’s new political paradigm.

If Burma seeks to emulate the political path followed by Gandhi, or Indira Gandhi, the former prime minister of India and Asia’s powerful unifier in the late 1960s, then the Middle Way can come to life in Burma. Suu Kyi grew up in India and was educated in England—she knows these stories better than most. Whether she will be a new Indira Gandhi, devoted to the common good and unity of all faiths, races, and religions, is yet to be seen.

India is positioning itself to be one of Asia’s powerhouses in the “Asian Century”, while China also prioritises regional influence. Burma, a small nation with a small population, will never achieve the level of political and economic esteem of its neighbours until the nation finds its own Middle Way—a sense of unity, hope, and purpose for all its inhabitants.